Here are more of the stories prompted by Gerry Cooperman’s post on Mass Birds:

Carolyn had several sparks — here is an early one:

I was watching the goldfinches, chickadees, etc. with my dad’s ancient binoculars and saw what turned out to be a large young cowbird begging and being fed by a tiny, very solicitous colorful bird. I got my color markers and drew exactly what I saw — a yellow bird with black head and yellow face. I dug out an old 1960s era book from the attic and saw that it was a Hooded Warbler. I have only seen one once since then and not in my yard. After seeing the picture and all the other birds that supposedly lived in my town, I got out of the house to look for them.

A Cowbird being fed by a Hooded Warbler sparked Carolyn’s birding. Here a Common Yellowthroat feeds two Cowbirds. photo by USFWS

Darin’s aunt launched him into birding:

I was fortunate enough to be “taken under wing” pun intended by my great Aunt Helen. I was about 10 when she told me she wanted to teach me about birds before I got into girls. She was a great lady and was once the “den mother” at Manometer Bird Observatory back in the 70’s. Some people might remember her, Helen Passano.

I grew up in Duxbury on a farm and we had a pond out front with a pair of Mute Swans. Their wings were clipped and I was around them all my formative years. I would have to go out in the winter and break the ice open to feed them cracked corn as a young boy. In the summers, Auntie Helen would write out test questions for me in regards to my adventures around the pond. I would have to draw ducks and other birds and answer specific things about them to pass. It was such a great learning experience. Then came that interest in girls she warned my about….and small block Chevrolets!

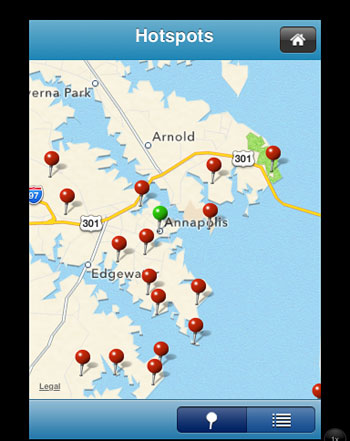

She was correct in her assessment, I am now in my mid forties and have passed on that love of birds to my wife Denise and my son Wil. We go on adventures about once a month all over Massachusetts. We keep lists upon lists and I really enjoy the time we all spend together. We even went to Machias Seal Island in Maine a few years ago and had our best birding trip we have ever had. The Razorbills and Atlantic Puffins so close you could almost touch them from inside the blinds!!! Absolutely amazing. They are both up to about 170 species on their life lists and they are constantly looking for a new entry.

I am so very lucky for my great Aunt Helen from 35 years ago.

Tom got started with NYC pigeons:

Having grown up for the best part of my early and teen years in a NYC Housing Projects in the 50s and 60s=2C we didn’t see much but pigeons.

But when I was around 12 I began to visit the American Museum of Natural History and found myself drawn to one diorama in particular and that was in The Great Hall of Birds on the first floor which I believe no longer exists in its original form.

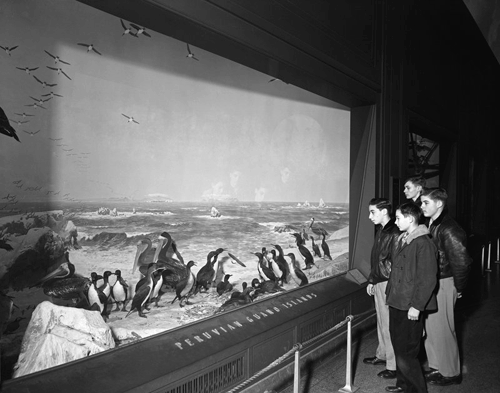

A diorama, similar to this in the American Museum of Natural History, sparked Tom’s interest in birding.

There were the ropes and the rail of a wooden ship looking out upon a stormy sea and hovering just above was a great seabird – a great albatross – and it held me in awe. At the same time at home we had a large illustrated edition of The Rime of The Ancient Mariner.

Between these two visions I began to wonder how this bird could provide me with such a feeling of peace every time I saw it at the museum and then give me the creeps whenever I opened the book and saw the arrow heading straight towards it.

In any case, it got me noticing birds and I really wanted to see live ones. So I began to find pheasants at the local cemetery ( St Michael’s in Queens- the other kids used them as archery targets) and later got a permit to visit the Jamaica Wildlife Refuge near Kennedy Airport ( we still called it Idlewild back then) – a long subway ride away.

And it’s been birds since then wherever I find them. And the pigeons? I still delight in their iridescent necks when the sun shines.

Thanks for letting me share and thanks to all who share their sightings. I would have never seen a Tufted Duck or Northern Lapwing without your kindness.

Dee relates how she and Bob “simmered” into birding:

For my husband Bob and I, getting into birding wasn’t so much a spark as a slow simmer. We met in college and liked to take long walks. Along the way, we’d notice a bird here and there. Being curious, when we got home,we would try to look the bird up in a guide only to discover that, not knowing what features to look for, we hadn’t noticed the ones we needed to identify the bird. So… we started taking the field guide with us – only to discover that we couldn’t see the bird well enough to make out the characteristics we needed. So… we started taking along a pair of binoculars – only to discover that one of us would get to see the bird, but by the time the other one got the binoculars the bird was gone. So… we started carrying the bird guide and two pair of binoculars. About that time, we realized that instead of looking at birds while we were taking walks, we were taking walks to look at birds. We had become birders.

Initial Post Responses: Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4

Join those who comment on what spark set them on their birding journey? Tell us about it with a comment below. You should sign up by RSS feed or via email to have future “spark” articles sent to you. Thanks